SEGMENT 2

Affective cartographies of invisible cities: sensitive mapping of spaces inhabited by

people experiencing homelessness

RESEARCH ETHICS

CAAE 77880024.2.0000.5582

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee since 2024 and follows all guidelines for ethical and humanized treatment, committed to people in situations of vulnerability.

REFERENCES

BRASIL

National Policy for the Homeless Population (Decree No. 7,053, 2009)

National Judicial Policy for Assistance to People Experiencing Homelessness (Resolution No. 605, 2024)

National Policy for Decent Work and Citizenship for the Homeless Population (Law No. 14,821, 2024)

This second segment aims to expand the methodological scope for the study of public spaces of collective use in Rio de Janeiro. It now seeks to analyze the configuration of “invisible” spaces produced by people experiencing homelessness in large cities, especially in Rio de Janeiro. This approach gains relevance based on findings from the first segment, “Cartographies of interrupted stories,” which began in late 2022. At that time, poverty increased. Unhoused individuals occupied more public and open spaces. This was largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A study cited in Resolution No. 605 of 13 December 2024 was conducted by the Brazilian Observatory of Public Policies on the Homeless Population (OBPopRua/POLOS-UFMG, a research group at the Federal University of Minas Gerais that studies policies for people without stable housing, also referred to as the homeless population). In 2013, there were 22,922 people experiencing homelessness. The numbers rose to 242,756 in December 2023. By 2024, they reached 309,998. Thus, the numbers increased more than tenfold over the last ten years.

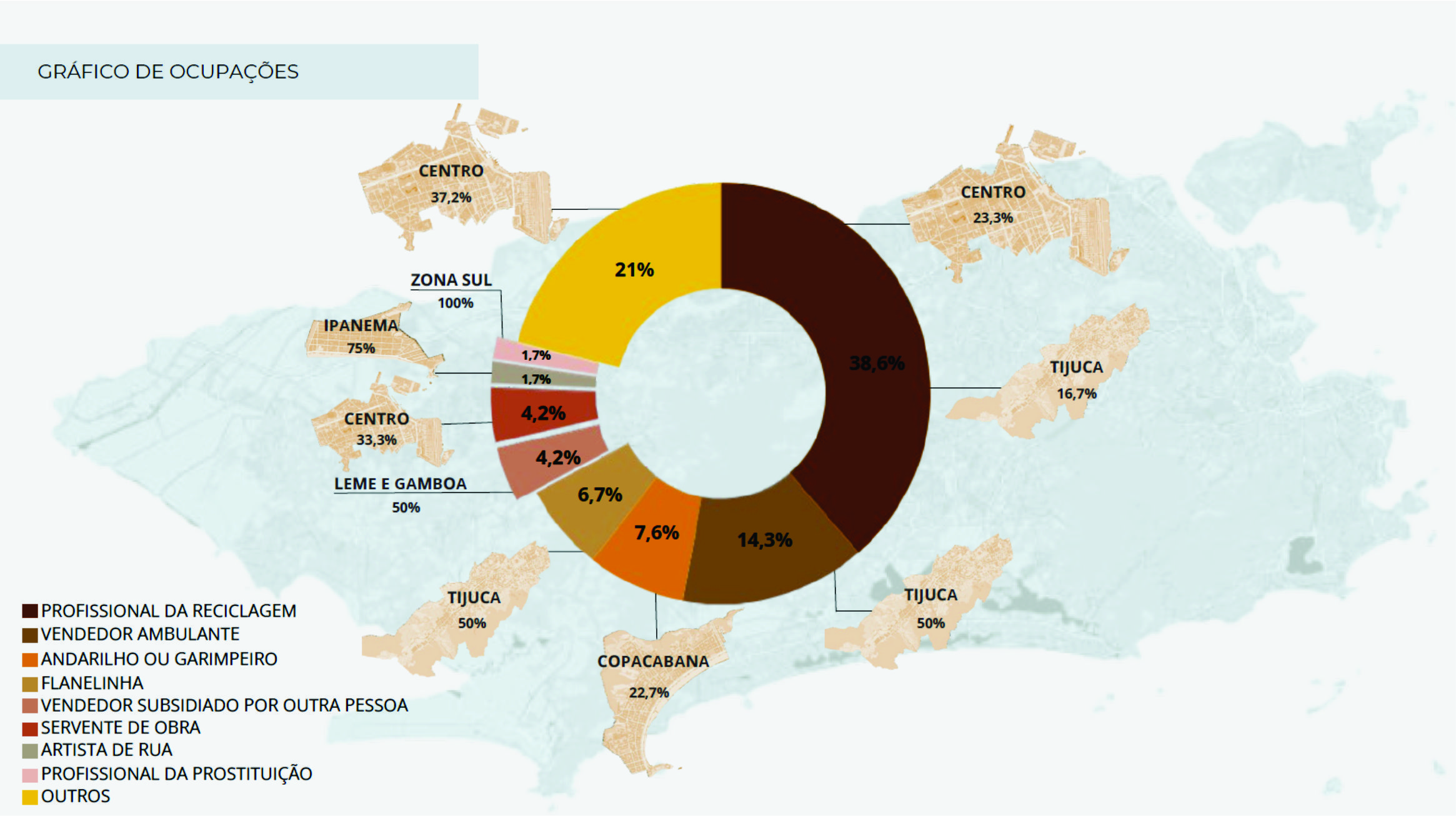

In Rio de Janeiro, the 2023 Homeless Population Census identified 7,865 individuals in the capital alone. This marked an increase of 8.5% compared to 2020. At that time, 78.6% engaged in some form of informal income-generating activity. Of these, 57.7% worked as collectors of recyclable materials. Another 20.7% worked as street vendors. 3% worked as informal parking attendants, and 3.5% were employed under formal labor contracts. It is impossible to ignore the impact of these figures on urban space.

Recognizing these dramatic increases, the research has treated these data as a starting point for analyzing the contemporary spatial context of the city of Rio de Janeiro since late 2023. This is in response to the significant increase in the number of people living on the streets without access to social justice. Through georeferencing and a qualitative approach involving semi-structured interviews, food provision, and direct support, the team gathers information in situ during nighttime rounds or drifts across several neighborhoods. These outings allow for the collection of names, length of time spent on the streets, the routes traveled throughout the day, and the forms of informal labor performed by these individuals.

Building from these field activities, the team develops affective cartographies that explore the possibility of “making free space habitable.” They also seek to identify, in the urban environment, the sensitive dimensions needed to protect these “aimless bodies.” The research maps the locations and neighborhoods where mobility constructs a territory, as well as the new meanings that these non-wandering maps evoke. To this end, tools such as Strava, MyMaps, and QGIS are used. Photographic records and ethnographic drawings are also included.

Alongside geospatial mapping, desk research is also part of the activities developed in this project. This includes data analysis, conjectures, and the mapping of narratives gathered through fieldwork with people experiencing homelessness, as well as the creation of geolocated maps. The project is supported by FAPERJ and CNPq. It collaborates with the Ombuds Office of the Regional Labor Court (1st Region) and includes participation from the NGO Só Vamos!.

The specific objectives of this phase of the research are:

> to define the types of appropriation and uses of the city within these “invisible cities“;

> to contribute to the development of cartographies that present sensitive data aligned with the need to revise urban planning practices;

> to develop a set of categories representing people experiencing homelessness in Rio de Janeiro;

> to enable an urban planning approach that accounts for the uses/appropriations and activities of the ordinary practitioners of physical space; and

> to train highly qualified researchers in the fields of Architecture and Urbanism.

Methodology

NIGHTTIME FIELDWORK

DIGITAL MAPPING

INTERVIEWS

ETHNOGRAPHIC RECORDS

PARTNERSHIPS

The project received support from FAPERJ (Rio de Janeiro Research Support Foundation, an agency funding research) and CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, a federal research funding agency).

RESEARCH ETHICS

Phase 1

PRODUction

Night map with spatial data from Segment 2, highlighting movements and forms of urban appropriation by people experiencing homelessness.

REFERences

Roberto DaMatta

A casa & a rua: espaço, cidadania, mulher e morte no Brasil (Rocco, 1997)

[The House and the Street: space, citizenship, women, and death in Brazil – gloss only]

–

Marco Antonio Mello; Arno Vogel

A favela e o asfalto: um estudo sobre a habitação no Rio de Janeiro (Zahar, 1980)

[The Favela and the Asphalt: a study of housing in Rio de Janeiro – gloss only]

–

Richard Sennett

O declínio do homem público (Companhia das Letras, 2014)

[The Fall of Public Man]

Nighttime Mapping Incursions / 2023–2025

Technologies and mapping procedures

The mapping process begins by defining routes for a rented van that seats about 10 people. The van circulates through neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro at night. Outings are planned based on reports from individuals or the media. When information about people experiencing homelessness or recyclable-material collection becomes public, the team discusses it. They then use this information for planning.

During each outing, the team records the locations of people encountered and marks them on Google’s interactive map, MyMaps. These data are later transferred to QGis, under an educational license issued by UFRJ. The Strava application is used to trace each route. It tracks the coordinator’s and team’s movements inside the van and on the streets. This process generates a dynamic 3D and 2D model.

Real-time georeferencing of the locations of people experiencing homelessness made nighttime incursions more precise and effective. For example, during an outing in the North Zone of Rio (Méier and Cachambi) on 21 November 2024, MyMaps displayed the exact number of people along each segment. It also showed sensitive information gathered through interviews. This enabled real-time data consolidation. All researchers could access this data at once, and later, others could as well.

The Google Maps ecosystem is a suite of mapping and GPS navigation services that allows users to search for, visualize, and get directions using integrated geographic data. This increases efficiency and enables collaboration among researchers.

Field incursions

Phase 1 of the segment “Affective cartographies of an invisible city” has been underway since late 2023. It aims to analyze specific strata of the city through direct inquiries in selected neighborhoods: Centro, Gamboa, Tijuca, Vila Isabel, Copacabana, Botafogo, Méier, and Cachambi. The research began with an initial sweep across the North, Central, and South Zones.

These inquiries showed from the start, during the first nighttime outing in downtown Rio, specifically in Cidade Nova, that a stratified methodological approach is needed. For this reason, the methodological process is structured around three sequential stages:

1> direct search for the location of people experiencing homelessness in predefined neighborhoods, through nighttime field outings supported by chartered transportation to ensure the team’s comfort and safety;

2> humanized support and direct dialogue with interlocutors, including the provision of food and explanatory material about the research;

3> application of semi-structured interviews, aimed at mapping nighttime points of permanence and daytime/afternoon movements, as well as recording personal narratives.

Social Methodology

The method, in its first phase (from late 2023 through 2024 and early 2025), has generated highly productive results. In 2024, the neighborhoods of Gamboa, Centro, Botafogo, Copacabana, Tijuca, and Vila Isabel were surveyed. More recently, in 2025, the neighborhoods of Méier, Bonsucesso, Cachambi, and Ramos were surveyed. It was confirmed that there is a routine or a motive underlying the act of wandering. This is expressed through activities as diverse as those practised by our interlocutors. It allows us to identify several categories of use of urban space.

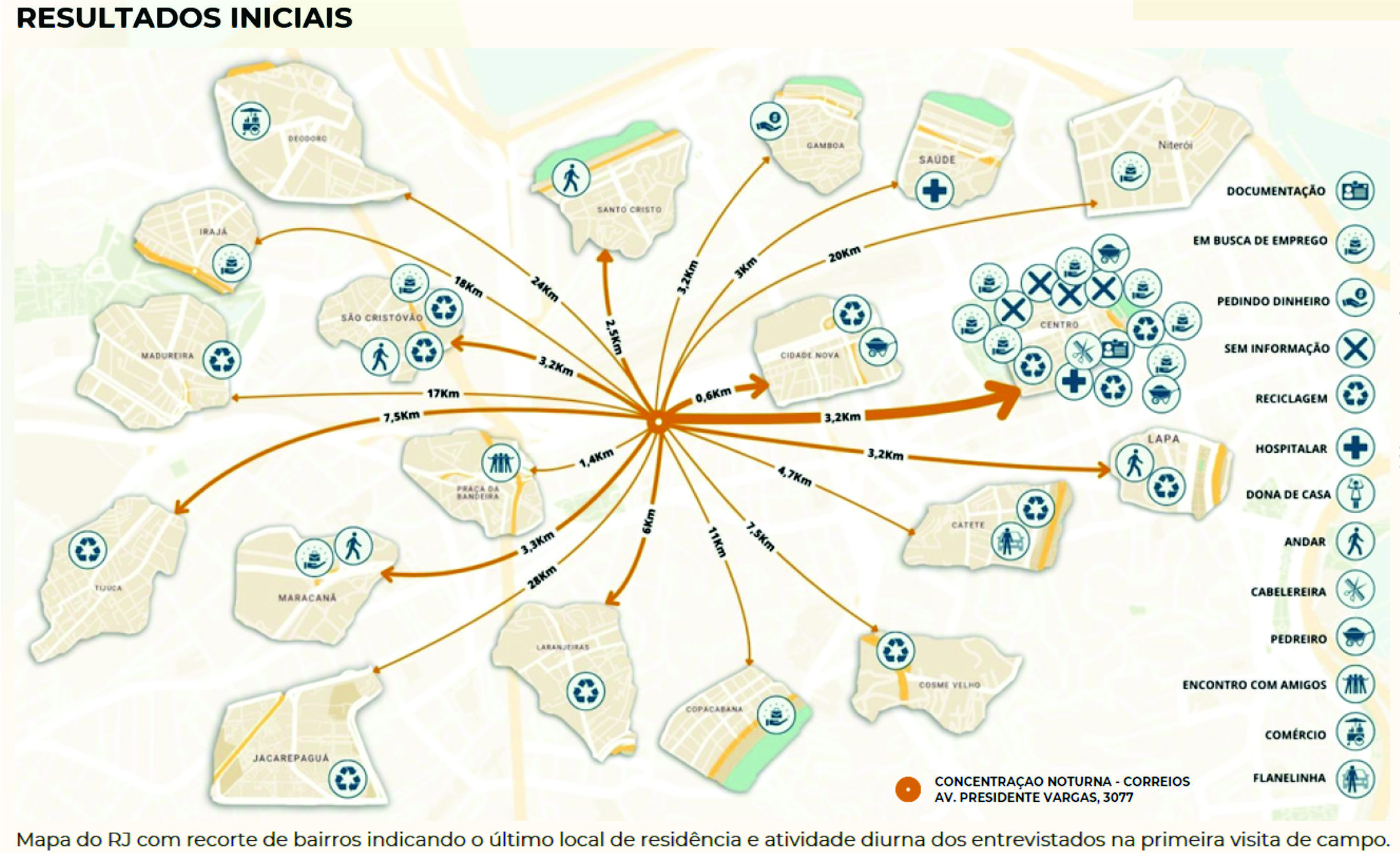

The routes described by people experiencing homelessness are part of the everyday landscape of Rio de Janeiro. For example, during the first nighttime outing on 18 December 2023, it became clear that interlocutors’ overnight stay at the same site (the Correios building in Cidade Nova, at the entrance to downtown Rio) did not mean they lived as an inert community. On the contrary, they used that location strategically to wander during the day, sometimes covering more than 10 km. They engaged in various forms of labor, such as collecting recyclable materials, working as informal parking attendants – flanelinhas –, performing as street artists, or selling food products.

This first phase will continue to be developed throughout 2025 and 2026 to gather responses from other areas of the city, such as the West Zone and the Baixada.

Results, urban categories, and new interpretations of the city

The notion of wandering as an uncommitted action was abolished, as many participants reported actions directly tied to daily work. The non-wandering maps show the distances people travel in a day before returning to shared overnight spots.

Many interlocutors see themselves not as “homeless,” but as street workers facing economic hardship and mobility issues. Most “pendular workers” live in the West Zone, Baixada Fluminense, or nearby cities, far from their street jobs.

The small sample, interviewed from early 2024 to mid-2025 (approximately 160 people), showed that official city occupation concepts do not align with the material reality of urban plans.

Building on these observations, the findings highlight significant gaps between urban policy expectations and the actual lived experiences of those working and residing in public spaces.

As a result of these documented gaps, the research has revealed new directions for understanding the “working class” and urban territoriality, due to several factors:

1> recognition that “street workers” fulfill a social role such as cleaning sidewalks, guarding commercial doors, or collecting recyclables;

2> group overnight stays (3+ people, residents over a year) consolidate symbolic and identity space.

3> defining archetypal characters illustrates recurring ways of maintaining urban space, as in Sennett’s early metropolitan essays (2014).

During this research period, the most common activities were: recycler (38.6%), street vendor (14.3%), wandering/odd jobs (7.6%), parking attendant (6.7%), subsidized seller (4.2%), construction worker (4.2%), street performer (1.7%), sex work (1.7%). The remaining 21% indicated “no activity” or “unemployed.” Figure 13 maps these occupational categories to neighborhoods where they are most practiced.

Phase 2

Participation and Visibility / 2025–2026

Phase 2, recently initiated, involves the following actions:

1> a “drawing kit” (notebooks and coloured pencils) was given to some Phase 1 interlocutors to return protagonism to research participants. These individuals are invited to create field notebooks to be shared with the research team later.

2> “self-detaching plastic stickers” were given to participants to place on surfaces they passed, highlighting the social crisis in city neighborhoods. The sticker’s short impact phrase – the city is not my home – aims to popularize the research, encourage rediscovery of urban spaces, and raise awareness of how people experiencing homelessness occupy them.

Some stickers were distributed during fieldwork in Tijuca, Bonsucesso, and Ramos (Rio de Janeiro) and in Manhattan (New York), in a phase led by the coordinator, who served as a Visiting Professor at Columbia University. Days later, stickers appeared near distribution sites and in areas of high commercial activity, highlighting the need for visibility along these routes.

By consolidating results from both research phases using graphic records (sketches), audiovisual documentation, interviews, and narrative refinement, data and tools will be finalized to interpret these invisible cities. This next step will use an affective cartography model currently under development to support both qualitative and quantitative understanding of urban life. life.

Conclusions

REFERences

Félix Guattari; Suely Rolnik

Micropolítica: cartografias do desejo (Vozes, 1986).

[Micropolitics: cartographies of desire – gloss only]

–

Richard Sennett

O declínio do homem público (Companhia das Letras, 2014)

[The fall of public man]

–

Vanessa Tiengo

O fenômeno população em situação de rua enquanto fruto do capitalismo (Textos & Contextos, 2018)

[The phenomenon of the homeless population as a product of capitalism – gloss only]

The synthesis of the method developed in “Affective cartographies of an invisible city“ will, by the end of the research period (projected for 2027), allow for a comprehensive representation through georeferenced graphic schemes and sensitive analyses that will reveal the circulation and permanence patterns of people experiencing homelessness in specific physical spaces of the city. This approach reinforces the value of sensory aspects of urban atmospheres and promotes the visibility of a city obscured by the absence of public policies or by inadequate urban planning. Through these sensitive analyses (articulated through narratives), it will be possible to map certain types of people “on the street,” as Tiengo (2018) suggests, since a character-figure can only be identified through bodily action in the city.

The study identified four archetypal characters, each revealing different strategies for navigating the city. These typologies provide new lenses for interpreting urban life, as detailed in the article “Urban narratives of invisible characters: the (de)public policies in the city of people experiencing homelessness.”

Shared attributes defined each character. These four “street types” represent the broader group, showing how people claim territory, coexist with others experiencing homelessness, and interact with the general public, creating their own territories. Guattari and Rolnik (1986, p. 323) define territory as “both a lived space and a perceived system where a subject feels at home” – translated freely by the author. These are the characters identified: the prospector, the extraordinary waste-picker, the traveling salesman, and the itinerant bookseller.